The Kenyan education system fights against memory, against acknowledging our past. But we need to recognize our pasts to grieve them, and in doing this work, we must tell these stories ourselves. For a long time, most of the narratives we have had about ourselves and our histories have either been the sanitized narratives of the neo-colonial state or the white-washed versions given by our colonial masters, and a lot has been lost in these versions. The stories we tell ourselves shape our esteem, decisions, and ultimately our destiny.

Thus, we must revisit our histories and uncover the various hidden truths that have long been buried. The past is all pervasive- we cannot escape it. It is part of who we are; our cultures, our behaviours, and manifests in all aspects of our day-to-day living. Knowing our true history connects us to our past and tap into a dimension of longitudinal meaning over time. Because of this, learning our true history is essential; history gives the past and the present visible form and meaning.

In doing this, history also allows us to see into the future by offering precedents for current behavior and forewarning us from repeating previous mistakes. But in a neoliberal education system, education is framed around investments in students as human capital, and the value of education is tied to the student’s prospects for future earnings. Such a limited approach to education raises concerns about the purpose of education and the relationship between schools, state governance, and democratic life.

Beyond education, neoliberal governance also results in the privatization of other public institutions and processes including urban planning. Harvey (1989) famously abstracted the spread of neoliberalism into urban planning as a shift from urban managerialism to urban entrepreneurialism. Whereas managerial cities had been primarily concerned with providing services and facilities to the urban population by the local administration, entrepreneurial cities in an era of increased interurban competition, had to focus on attracting investment and employment more than ever before.

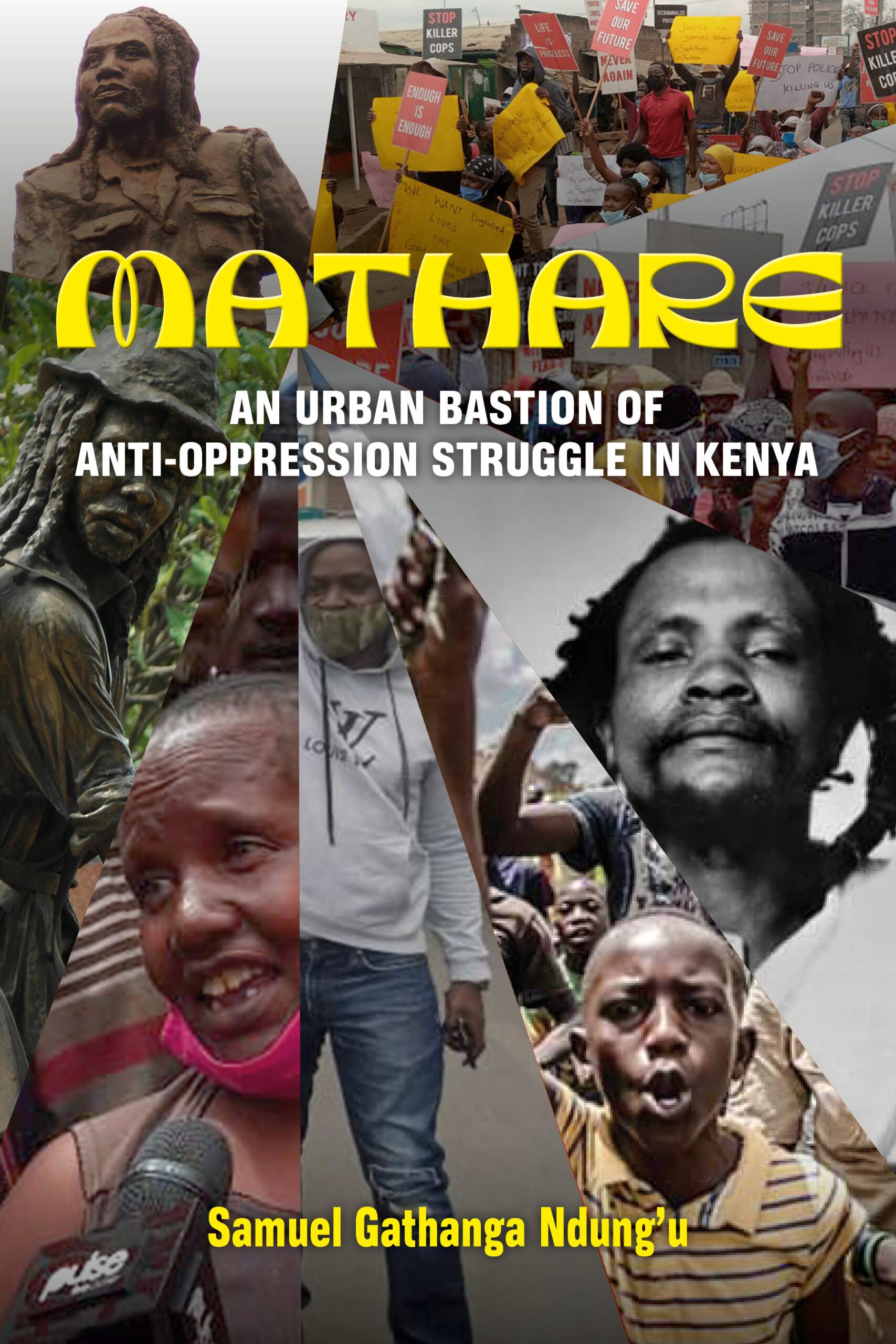

The consequent de-democratization of urban policies has left out a big chunk of the urban population from decision-making processes. This population continues to be threatened by unaffordable urban developments in the form of evictions and neglect. It is against this backdrop that Mathare, the urban bastion of the anti-oppression struggle in Kenya, exists.

Despite its role in the fight for Kenya’s independence and the post-colonial struggles for liberation, Mathare’s story is often overlooked. As Gathanga writes in his book, most people outside the settlement associate the name Mathare with the mental hospital bordering the settlement. For others, their narrative of Mathare is one of pity, considering that the place is known to house the urban poor.

Reviews

Clear filtersThere are no reviews yet.